In the twilight, the door slowly rotated until it stopped to the impression of weight and age. Blanca timidly stepped forward and said “hola?”*. Silence greeted her from the other side of the door. She knocked once on the door. Again the wood magnified the sound and seemed to mock her paltry efforts to get attention in such an auspicious place of worship. There was still no response. The light was quickly fading, the lights of Granada were streets away and the sound of the evening shoppers was now a distant memory. In this half-light we found a doorbell located to the left of the doorway. Its shrill note seemed out of place in this place of quiet prayer. Momentarily a frail voice came from the other side of the door “que quieres?” (“what do you want?), this greeting sounded more like an accusation to the shoppers.

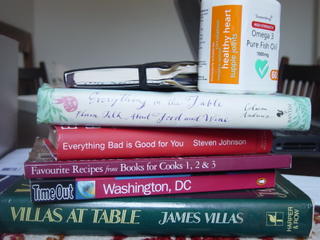

A month earlier… in November this year, Amanda Hesser wrote an article on the Thermomix for the New York Times. In this she explained the somewhat “counterintuitive” marketing strategy used by the firm. The product is not sold in shops, it is sold through introduction (somewhat like Tupperware) and the US supplier was less than forthcoming with information. To summarise, she thought the service was bad. Up until yesterday, I would have agreed with her that this was certainly unusual customer service.

In Spain, there is a long tradition of nuns producing sweets. The “dulces conventuales”, whilst not specific to Andalucía, are more important here due to the number of convents and range of sweets that are produced. Two historical facts need to be examined in understanding the development of these sweets.

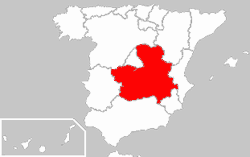

[i] Firstly, Granada was the last Moorish kingdom to be reconquered by the Catholic Monarchs. In order to celebrate this throughout the Christian world, from the moment of the victory both civil and religious authorities worked to Christianise the city. This was to such an extent that a number of years later, the archbishop of Granada had to put a break on the construction of religious communities. Nevertheless, by the end of the 16th century, there was approximately 1 religious person for every 30 inhabitants, or 622 nuns and 585 monks.

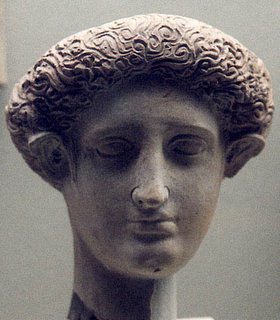

One of the monasteries that was founded was called “El Monasterio de la Madre Dios” (by the full name; Real Casa de la Madre de Dios, de la Orden de la Caballería de Santiago de España; known as El Convento de las Comandoras de Santiago (The Convent of the Commanders of Santiago)). It was opened by Queen Isabella in 1501. The Order of Santiago itself dates back to 1175, when it was founded by Pedro Fernandez de Fuenteencalada whom, along with 12 other knights of the order, wanted somewhere to protect his wife and children whilst he was fighting the Muslims. Today live 20 nuns in the monastery, 11 of whom come from India.

The second fact that must be considered is the [ii] “desamortización” (disentitlement). This is an economic process that ran in Spain from the end of the 18th century and culminated in the middle of the 20th. It consisted of putting on the market, through means of public auction, the non-productive lands and wealth that were in the hands of the “dead hands” (typically the church and religious orders that had accumulated them through donations and wills). The aim of the desamortización was to grow the national wealth and develop a bourgeoisie middle class of landowners.

[iii] The process of desamortización was used to its fullest by Juan Álvarez Mendizábal, the first minister of Isabel II of Spain. Isabel II proclaimed queen at the age of 3 after the death of her father Fernanado VII. Her accession was disputed by her uncle Carlos María Isidro de Borbón, whom, citing the law (Ley Sálica) that there could be no female heir to the thrown, claimed the thrown for himself. During the war that followed; the First Carlist War (1833-1840), Isabell came to represent the liberal, moderate “nuevo orden”, whilst her uncle, the traditional, religious “antiguo orden”. Mendizábal sold many religious lands in order to finance Isabell’s victory. It is said that the loss of these lands and wealth forced many convents into the production of “dulces convetuales” and sowing in order to earn money.

Most of the recipes are egg based. Convents are often donated a large amount of egg yolks from surrounding wine producers who use the whites during the clarifying process. Additionally, Irene tells me that there is a strong tradition in the south of Spain of gifting eggs to the convents in order that they pray for no rain on wedding days. Blancs and I didn’t do this, but it didn’t rain.

The nuns of the cloister of Santiago are famed for their candied and preserved fruits. There are no written recipes. The sweets are made from memory, based upon recipes that have been maintained over centuries. There combine a cultural and gastronomic legacy and it is said that only the patience and devotion of the nuns can bring out the flavour of the sweets.

Nevertheless, here is a recipe for “Glorias”…

1 kg ground almonds

1 ¾ kg sugar

Zest of 3 lemons

1 kg Water

Mix the almond, ¾ kg sugar and lemon. Make a strong syrup by heating the water and sugar. Pour into the almond mixture. Beat until the mixture doesn't stick to the side of the dish. Once cool, make into little balls and cook in the oven until golden.

The nuns of Santiago live by a rule that they can not see people; this explains their unique form of salesmanship. At a more secular level, Ferran Adria swears by the Thermomix and there are approximately 200,000 sold every year in Spain and Italy. Whether it’s the mix of religion, history and economic reform or just something in the water… either way both have immense success in Spain.

¡Feliz Navidad!

Vocab builder:

- escarchada – candied

- confitura – preserved

- rosco – ring-shaped cake

- bollos – bread rolls

- erario – treasury

- subasta – auction

- avituallamiento – provisioning

- lote – plot of land

- puja - bidding

Sources:

[i] Lola Quesada Nieto “Dulces de los Conventos de Clausura de Granada y su Provincia”

[ii] Wikipedia http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Desamortizaci%C3%B3n “Desamortización”

[iii] Ramón Tamales y Antonio Rueda “Introducción a la economía española” (26ª edición)

* We have since found out that the traditional greeting is an Ave Maria. This may explain the reception we met.